The Brief – September

|

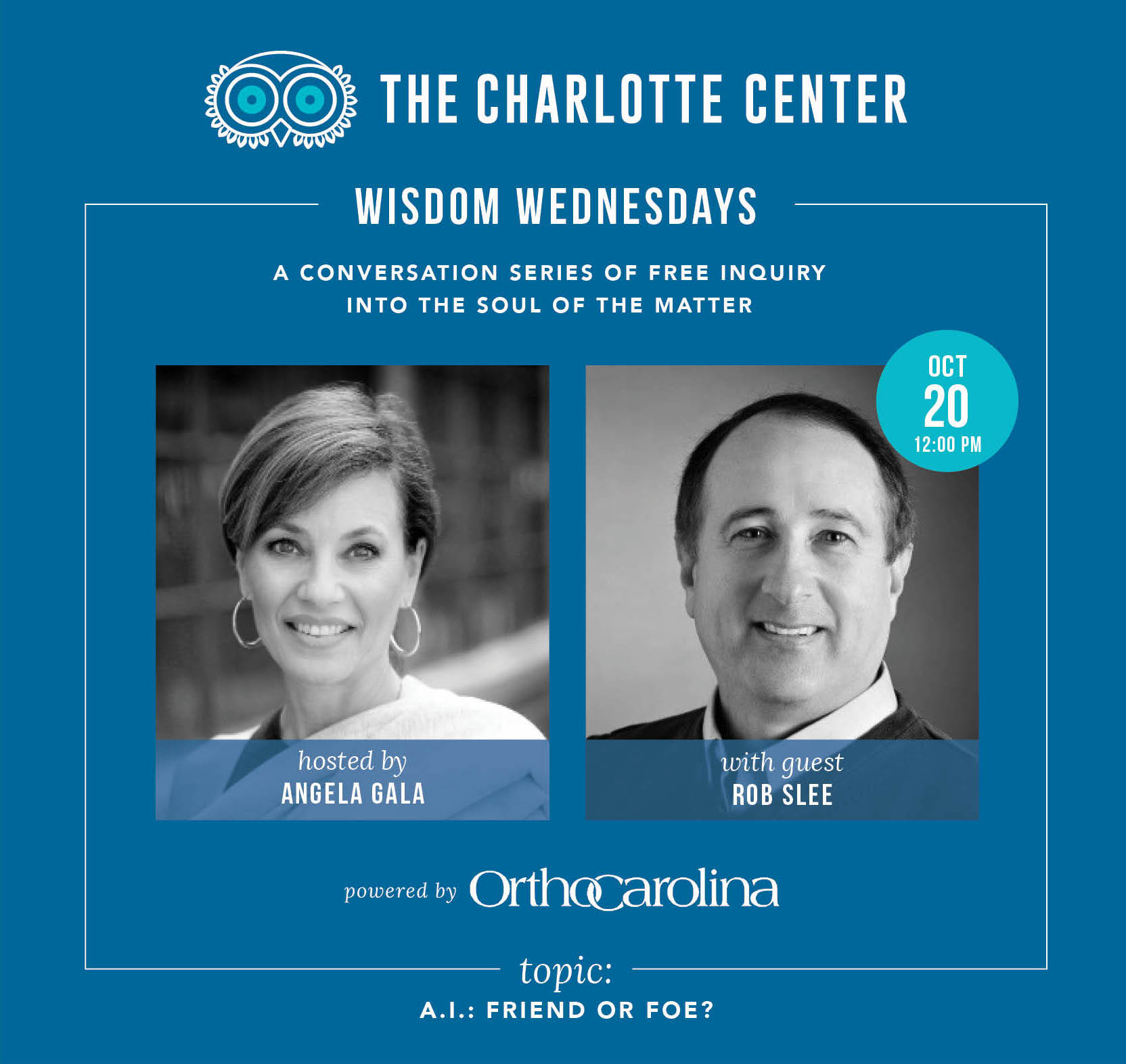

SEPTEMBER 2021 CONTENT Choose Change Wisdom Wednesday with SKY A.I. Co-Founder Rob Slee 5 Questions with Designer and Artist Dimeji Onafuwa, Ph.D. A Word JULY 2021 Choose Change Fall has arrived. We are feeling the temperature drop and seeing less of the sun. Change, seasonal or otherwise, can trigger a range of responses. A shift you might celebrate, others will resent, as conveyed in Equinox, the poetic piece below.

fading daylight hints its approaching the rustling cues my lament and loathing hustled, leaves surrender verdant hues a pall befalls every branch in view. its cooled breath, a cause to brood déjà vu dreading of a bluest mood. never ushered, seemingly flung in the season liked least of them alas, here again: autumn.

ava wood

While it is hard to let go of a perceived good thing, outrage and resistance are generally futile. Things come and go. They evolve and revolve. That’s life on Earth. Seething in silence or with primal screams, we can try pushing against change, to little avail.

The Charlotte Center contended with its share of fluctuating circumstances while planning for The Forum earlier this month. A string of events required the team and our collaborators to adapt and change plans more than once leading to a wonderful event. As Darwin theorized, “It is not the strongest of the species that survive, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change.”

While change can be difficult, loosening our grip on the status quo is often wise. Grieve the real or perceived loss, hold on to lessons from the experience, and then explore what the next stage has to offer. Whether it’s saying sayōnara to summer, adapting to evolving CDC Covid-19 guidelines or digesting shifts in new Census data, we all struggle dealing with disruptions to what was, moving on, and navigating what’s unfamiliar and seems a risk. What change are you grappling with? What is it you’re really trying to hold on to?

“The changes we dread most may contain our salvation.”

— Barbara Kingsolver, American novelist, essayist and poet 5 Questions • Dimeji Onafuwa, Ph.D. An interview with the Nigerian-born designer, researcher, and artist who resides in Seattle, yet still calls Charlotte home

BY VALAIDA FULLWOOD

Dr. Dimeji Onafuwa has many talents, and painting is among them. Tilling passion from his African heart and American soil, he cultivates evocative and emotional scenes of assimilation. Onafuwa uses color boldly and simply to create a luminous quality of melancholia, allowing the viewer a powerful sense of human-ness and a presence of the spiritual. He draws inspiration from Henri Matisse, Fauvism, the 1960s San Francisco Bay Area figurative artists, as well as concepts from the Yoruba language. Examples include ‘Ona,’ meaning embellishment of form; ‘Ara,’ creativity; ‘Era,’ improvisation; and ‘Pipe,’ equaling completeness.

Dimeji is represented by Sozo Gallery in Charlotte, and his work is currently part of the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture exhibit: Visual Vanguard: An Exhibition of Contemporary Black Carolina Artists. He is often invited to speak at conferences, on podcasts, and at workshops globally on topics as varied as art, alternative economics, transition design, diversity and inclusion in design, the commons, allyship, and algorithmic bias.

Tell me, what drew you to your doctoral studies and work in Design?

One of the things that took me into my field of study is that I started to think: How might designers participate in solving big, complex problems or wicked problems—those with such complexities that every time you try to solve it, it causes a new problem? I also wondered how we might articulate to others the way designers solve these problems and be able to use that as a framework for problem solving.

That led me to my doctoral work in community-driven systemic change in a field called Transition Design, which looks at systemic and intervention-level problem solving. Specifically, I studied microeconomic theory in what’s called “the commons” from the work of Elinor Ostrom. It looks at new ways of negotiating resources that are vital to our collective survival. That work bled into inclusive UX design practices, and that’s where I find myself today.

You’ve traveled all over and lived in several major cities—Lagos, Pittsburgh, Seattle, and Portland, to name a few. What do you miss about Charlotte?

Well, Charlotte is home and someone once told me, Charlotte was kind to me. It is the closest I know to home among all the cities in the United States that I’ve lived in or visited. There’s something about it that connects with my growing up in Lagos, Nigeria. I don’t know if it’s the soil or the people that connects me to my birth country. The other thing I really love about this city is that it is a city that makes space for Black people. You see us in upwardly mobile roles, in leadership roles, in running community-driven initiatives, and the city is all better or it. It feels like a city that acknowledges my right to participate in its governance and its improvement. That’s something I love about it.

It’s a city I never left. I still have ties in Charlotte. I still see Charlotte as my hometown and still come back quite often. I try to keep as many connections in Charlotte as I can.

On the converse, what would you like to see more of in Charlotte that’s present in other cities?

While I know Charlotte has changed a lot since I decided to live elsewhere, I still come back often and keep my ears to its heartbeat. When I think about Charlotte, at least my experience with the city, one thing I notice is that Charlotte is way more amazing than it lets on. It’s almost like it needs a sense of gusto. It needs to believe that it’s a force to be reckoned with.

Charlotte is a major city that participates in driving the future of this country. Even so, I feel there’s a timidness to the way that Charlotteans go about their everyday life, because there’s still that chip on the shoulder. We feel like a small city. We feel like a lesser sibling to Atlanta. But Charlotte has arrived and needs to recognize it has arrived.

I also think we have these progressive initiatives and ideas that Charlotte as a city has been driving the past few years. We cannot ease up off the pedal. We have to continue pressing hard on these ideas, because this is what makes great cities.

What’s your happy place and why?

My happy place is at home in my studio on a Saturday or Sunday morning, because my agenda is cleared. My focus is the work. The disruption is not there. It’s almost like that moment of meditation, being able to think about the work but also reflect on other things that I haven’t had the luxury of during the week. That’s my happy place.

In your bio, you say, as an artist, you draw on concepts from the Yoruba language. Please tell me more about these principles and their meaning.

Great! I will use this as an opportunity to attempt to connect art with design, which is dangerous because they are quite different. One of the things we’ve learned in design school, and I’ve been in design school from undergrad through the graduate level, is that design is something that is tied to modernity—Western modernity, at that. A lot of art is also perceived that way. “Good art” is seen as art from the modern period. I’m not talking about modern art, but art from the post-industrialization era. People think that any art that comes from a culture that is seen as “naïve” is not really art. So it is often relegated to things like craft. Design is very much thought of that way.

We have formed these principles of art, and we’ve also formed these principles of design. These are Western principles; however, if you look at 15th-century work of the Ife culture in southwest Nigeria, it doesn’t align. When Europeans first encountered this art, they were befuddled. They could not believe, to paraphrase, that a naïve and savage culture could create such exquisite art.

There are distinct things that drive the creation of art within the Yoruba culture, and these have sustained through history and remain consistent even today. I reference these Yoruba words and principles. Other artists have drawn from these principles, which as observed in Yoruba craft and Yoruba art. These include ere, improvisation; ojú ona, design consciousness; ojú-inú, the inner eye, where you are able to see different layers of meaning in a work you’re creating; and itutu, coolness, where the work has a sense of calmness and coolness, not in terms of a color choice, but its mood.

It’s time to tell that story, to be our own historians. There is something to be said about the way we create art that the world is not acknowledging. You see a lot of these principles in African American art as well where there’s that art culture that has transcended the oceans and has carried over into the Western world and deserves to be acknowledged. Follow Dr. Dimeji Onafuwa!

About The Charlotte Center WHERE THE CURIOUS ENGAGE FOR GOOD.

Centered in the humanities (poetry, literature, history, religion, philosophy, the arts), our programs deepen human connection and strengthen personal and civic agency.

The more we know about ourselves, the wiser we are in what we do.

OUR FUTURE DEPENDS ON IT. gratitude to our sponsors

The Charlotte Center operates with support from financial donors and generous sponsors such as those listed above and you. A WORD I am not sure that I exist, actually. I am all the writers that I have read, all the people that I have met, all the women that I have loved; all the cities I have visited.

JORGE LUIS BORGES Argentine essayist and poet Our Contact Information The Charlotte Center is a non-profit 501(c)3 organization.

Word to the Wise is compiled and edited monthly by Valaida Fullwood Design by Goldenrod Design Co. |